Aveek Bhattacharya | Twitter

Aveek Bhattacharya is Chief Economist at the Social Market Foundation, a cross-party think tank. He holds a PhD from the London School of Economics, comparing education policy in Scotland and England.

The key to any good piece of utopianism, in fiction or political writing, is to clearly establish the ground rules. Which constraints do we keep in place, and which do we imagine away? Here are the parameters I am setting myself for this fantasy programme for government: I cannot take on any powers that the devolved administration does not already have and I cannot spend unlimited money. The coming years are going to be extremely challenging for the Scottish Government, facing growing demands and restricted funding from Westminster. I suspect the proposals I am making here will stretch the Budget, but hopefully not too far.

What makes this a fantasy is that I am not going to worry too much about political feasibility and implementation. The Scotland I envisage is one with a bigger state that does more to protect and support its citizens, and takes more in taxes in return. That may turn out to be a hard sell, and it will certainly take more than the single year a programme for government is meant to cover, but those are not my problems for now.

‘Building back better’ – recovering from the COVID-19 crisis and using what we have learned to develop a better society – should be central to the programme for government. I would start with mental health. It was heartening to see the topic receive such attention during the election campaign, as one of the most significant things government can do to affect people’s wellbeing. Waiting times are too long, and there is evidence of a spike in rates of depression and anxiety during the pandemic, which seems to have persisted through 2021. This needs a substantial response, and I would favour the guarantee of some form of support even for those with mild to moderate issues within six weeks proposed by the Mental Health Foundation Scotland.

Education will also be central to the pandemic recovery. While the terms ‘catch up’ and ‘learning loss’ are controversial, it is clear that young people have been significantly disadvantaged by the disruption to their lives and schooling. The Westminster government has rightly been criticised for its “feeble” response, leading to the resignation of education recovery commissioner Kevan Collins, but at least he was hired in the first place. Planned catch up spending in Scotland is of a similar magnitude to England, but barely a tenth of the amount committed in countries like the US and Netherlands. I would commission an independent assessment of school needs (perhaps led by Collins, if we feel like being mischievous), as was initially done in England, but actually follow its recommendations in allocating resources in the months and years to come.

Unfortunately, even with the best possible efforts, schools are unlikely to protect every child from damage to their life prospects. A universal job and training guarantee, rolled out initially to young people but extended to the whole working population could mitigate economic ‘scarring’ from the crisis. By ensuring every person is entitled to a minimally decent job, through public subsidy or direct government employment, it would avoid harmful lengthy spells of unemployment and give workers an alternative to the worst insecure and exploitative jobs. This should be part of a broader effort to support and promote adult education and training: the Scottish Government should significantly increase the scale of its Individual Training Accounts (currently worth £200 a year) to be closer to the £9,000 allowance proposed by the Independent Commission on Lifelong Learning.

Another major educational issue exposed by the pandemic are the limitations of our school qualifications system. The chaos and dissatisfaction that have accompanied the last two sets of National and Higher results have shed light on the pressures and inequities of the way we do assessments: three sets of qualifications squeezed into three years, assessed largely through high-stakes exams that encourage teaching to the test. Worse still, this approach largely contradicts the approach to learning and assessment the Curriculum for Excellence tries to promote up to the age of 15. Those curriculum reforms were launched on the back of an impressive consultative process – the 2002 “national debate on education” – in which 20,000 people are estimated to have participated. The Scottish Government should build on that history by convening a citizens’ assembly to consider the appropriate objectives of school assessments and qualifications, and how best to achieve them. A randomly selected group should be presented with evidence and expert testimony reflecting different perspectives on the issue and encouraged to debate them in order to reach some degree of consensus.

The government’s openness to deliberative and participatory democracy is admirable, and has the potential to increase people’s engagement and sense of empowerment from politics while ensuring the public debate is better informed by expertise. It has already gathered one citizens’ assembly with an open-ended brief to provide a vision for Scotland’s future, and the SNP manifesto promised more in the coming parliament. The tricky thing – as France is learning from its climate assembly – is ensuring that these initiatives lead to action and do not just end up as talking shops. Hopefully tasking the citizens’ assembly to tackle as specific and pressing a topic as school qualifications will lead to clear recommendations, which the government should be compelled to respond to, if not adopt in full. If that experiment goes well, it should be the model for addressing other contentious and/or technical policy issues, such as social care or criminal justice reform.

This parliament should also be an opportunity to accelerate progress towards the target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. The jobs and training initiatives outlined above should contribute to building green infrastructure, such as electric vehicle charging points, decarbonising heating for homes and buildings and cycle routes. The Government should also raise taxes on activities that are bad for the environment, with higher (not lower as initially proposed) air departure tax and a move to road pricing.

Those policies will raise some revenue, but to help pay for the stronger safety net and more generous public services I envisage, the Scottish Government should seek to reform property taxes, from which it raises proportionately less than its counterparts in England and Wales. House price rises have increased household wealth by £10,000 per person in Scotland over the course of the pandemic and that windfall ought to be shared with those that face struggles emerging from the crisis. While not quite as bad as other parts of the UK, Scottish council tax is regressive and outdated. Moreover, the commercial property tax regime – business rates – creates inefficiencies and disincentivises investment. Both are ripe for change, and in an ideal world I would seek to integrate them into a single land value tax, removing the distortions they cause. As the name suggests, this would tax people according to the estimated value of the land they own, rather than the value of the buildings that sit on top of it. That should encourage people to use land more effectively according to its best purpose. It will also increase taxes on those owning large properties in more expensive (and therefore affluent) parts of the country.

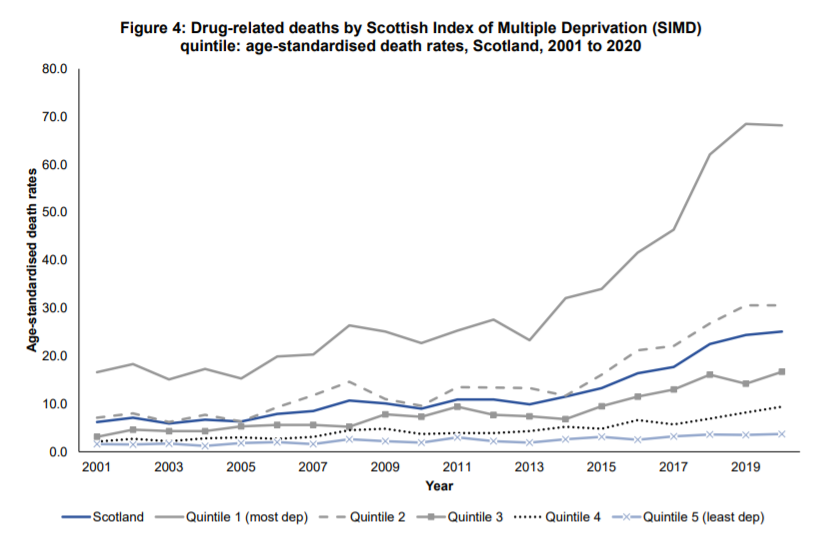

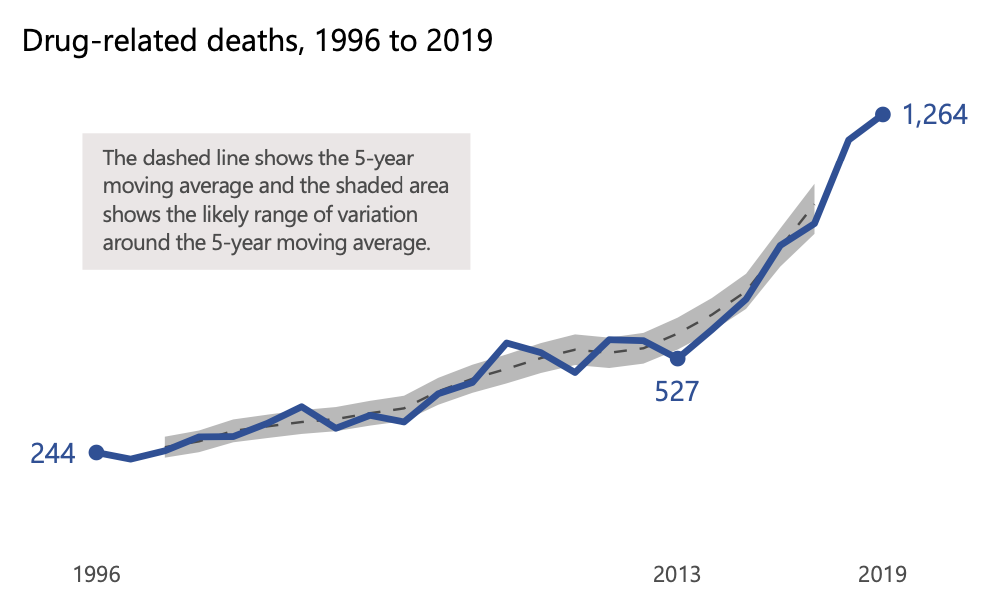

The fact that this already feels like an extremely ambitious programme for government despite that fact I have not even mentioned economic productivity, welfare, drugs, alcohol, obesity, the prison population, childcare or housing highlights the scale of the challenge facing the Scottish Government. There is a lot to do and limited time and resources to do it with. We can only wish them luck.